In 2023 I participated in the University Design Forum Research Group’s project on student residences. This project started from the proposition that ‘the vast majority of purpose-build student residences are the same’ . It culminated in this 2025 report.

The implied question (yes they are, but can we do better?) was a good one. The report, in my view, does an excellent job in addressing the question, outlining the depressing ubiquity of cluster flat and studio developments.

However, the innate conservatism of student housing developments in the UK (both university and private sector led) is not just about typology but also about site acquisition, construction methods and the mixed use of buildings. If we look at Europe we see considerably more innovation, especially with regard to long term regeneration sites.

Meanwhile use

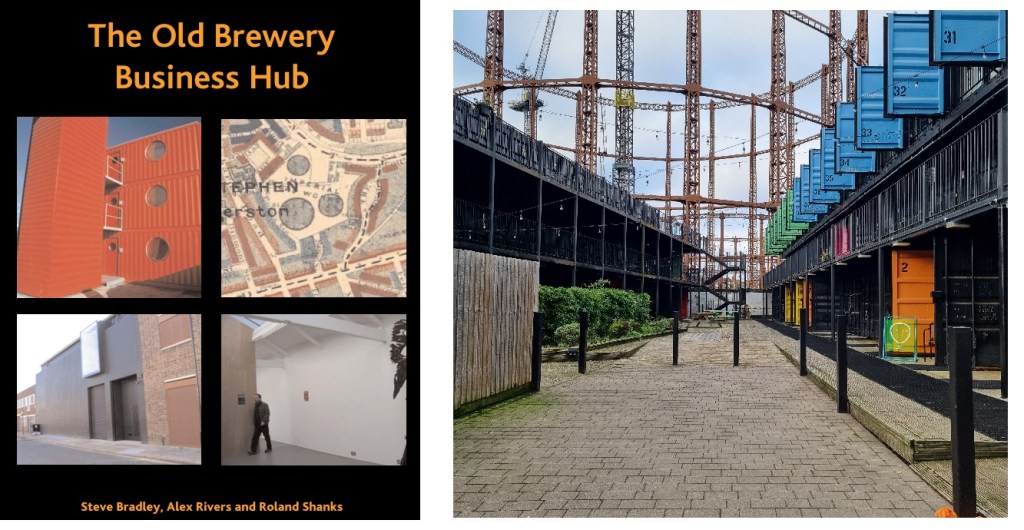

The regeneration of major sites can take decades to complete. In the Netherlands they often use student housing built out of shipping containers for meanwhile use on these sites. Shipping containers are designed to be stacked up to five storeys high with no need for supporting framework or substantial foundations. They are thus ideally designed for temporary use.

Other advantages of using them for student housing include:

- Being temporary housing designed to house students for one academic year at a time, means that when the site is ready for permanent development, it can be vacated relatively easily.

- When permanent development on the site is ready to take place, the containers can either be dismantled and moved to another site or incorporated into permanent structures . Many permanent PBSA developments and hotels have used shipping containers as building blocks within traditional steel frames.

- Moving students to a vacant site revitalises it. Their presence supports commercial uses like cafes and shops, enhancing amenities for future residents of the permanent developments.

- They can be built cheaply. More importantly land costs could be very low. From the landowners point of view, a token rent is better than no rent especially if the presence of students brings other advantages to the site. On that basis, it may be possible to use them as part of a solution to the affordability crisis of student housing.

Don’t they look horrible?

Shipping container housing can be terrible. Within the UK there have been examples of it being used for social housing with very mixed results. However, the same can be said of buildings made with glass , steel or brick. Shipping containers are just another building material. They can be used to build either beautiful or ugly buildings.

Aren’t they just steel boxes- baking in hot weather and freezing in cold?

Shipping containers have been used as a building material for student housing in a wide variety of climates, from Norway, through to Australia. Provided they are insulated and ventilated well, they are extremely comfortable.

So what are the prospects of this happening in the UK?

When I studied for my Masters in Urban Regeneration, we were asked to choose a vacant site and model what we would build on it, including a site valuation (using a Land Residual Valuation). I persuaded my group to choose a vacant site next to the Regents Canal in East London and model shipping container offices on it. Several years later, this is exactly what was developed on the site. Initially it was developed with temporary planning permission but after ten years this had been converted to permanent.

There is no shortage of developments being built in the UK using demountable shipping containers. One of the pioneers of this is Container City, who have won design awards for some of their developments (notably the Roundhouse in Camden). Similarly, Box Parks have appeared on various regeneration sites from Croydon to Liverpool.

What hasn’t been attempted on a widespread scale in the UK is student housing built with shipping containers (other than as a building block in permanent structures).

In some ways this is understandable. The majority of new PBSA that has been built recently by the private sector has been aimed not at those that need housing the most but at those that can afford the most. Building with demountable shipping containers for these types of development is not the natural choice.

However, for universities, especially those that are closely attuned to the regeneration aims of their local or regional government, this approach could pay dividends. Demountable shipping containers don’t really work for permanent housing (you can’t put up shelves or knock through walls) but for students they are ideal. For many the industrial aesthetic is itself part of the appeal. They are or can be cool.

Just as, or perhaps even more, importantly, they could deliver affordable student housing at scale. Within today’s land markets this has remained an almost unachievable goal for universities.

Surely it’s now time to look at the success of this model in Europe and see whether it could be applied in the UK?

Leave a comment