The starting point for any project should always be the same. What need does this project address? Can this need be quantified and measured? Are the resources needed to deliver the project justified by the benefits it will deliver? And finally, what could go wrong?

For all of this, you need a solid evidence base.

Developing the evidence base

One effective way to build an evidence base is by conducting surveys. When responding to an event or opportunity, it’s also useful to understand its historical and quantitative context. Regular surveys, done annually or bi-annually, can help you do this. Like going to the doctor for a regular health check up, the surveys also help monitor emerging issues, allowing you to take corrective action before they turn into major problems.

Using other datasets

The first step in planning a survey is to see what information is already available and how reliable those sources are. Is your survey repeating what’s already been done, or is it uncovering new insights? Lastly, can existing information and datasets enhance your own survey?

For example, if you are conducting an accommodation survey, there is extensive HESA (Higher Education Statistics Agency) data on which students live in which postcodes. This data allows you to weight your own survey responses (which will be a sample of the overall population represented by the HESA dataset).

Similarly, you can compare postcode rental data with your survey results. If your students report rents in the lower quartile for a postcode, it may indicate the trade-offs they are making between quality (if rent is a proxy for quality) and location. You can also use IMD (Index of Multiple Deprivation) data for similar analysis.

Again this analysis can be cross referenced against satisfaction scores, allowing you to see whether students are making the best decisions when choosing their housing. That, in turn, can influence the advice you give to them.

London Student Accommodation Surveys

At the University of London, I designed, promoted and analysed bi-annual student accommodation surveys. These were initially conducted to assess the state of the market and students satisfaction with both their housing and the support offered to them by the University in finding it. Later, these surveys became key to establishing the evidence base for Policy H15 of the London Plan.

The 2015 survey is still hosted on the london.gov website here.

The surveys were mainly publicised via block emails. Both Colleges within the University of London federation and those outside were invited to participate. I produced individual benchmarking reports for each College so that they could see how their results compared with overall results.

The surveys were online, using routing questions so that students were only asked questions appropriate to their specific circumstances ( the design of this was quite tricky).

To encourage participation we offered token prizes. I don’t know how much the prizes motivated students to take part ( I suspect not much) but the aim was to leave no stone unturned to get the maximum response possible. In our best year (2015), we received over 6,000 responses and in our worst, I think we still have managed over 2,000. I have yet to see any other student accommodation surveys with comparable results.

Dealing with bias

Surveys are voluntary, and participants choose to take part. This leads to questions about why people decide to participate. You might think that those looking to “blow off steam” would take part more often, making the situation seem bleaker than it actually is.

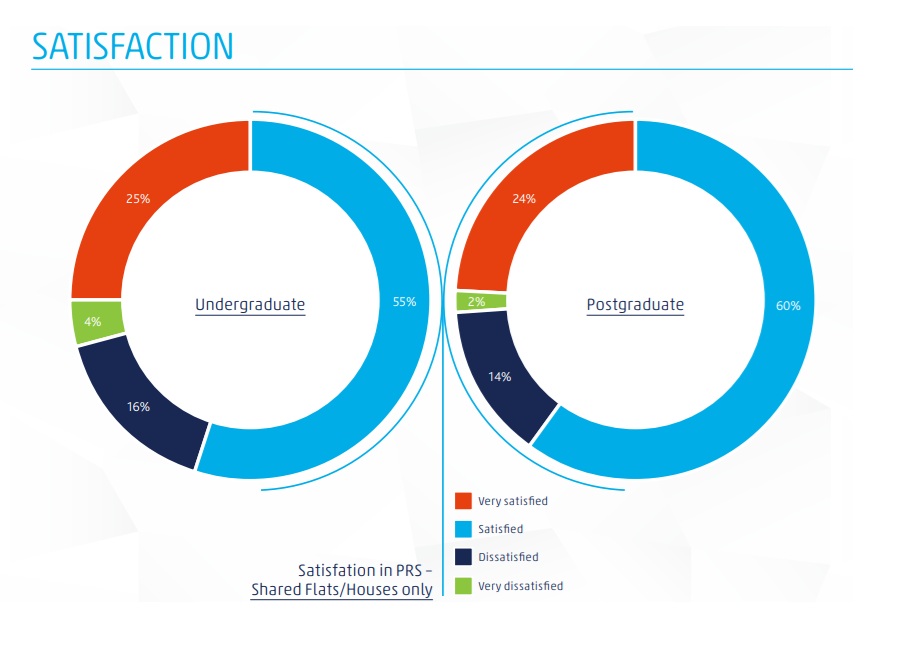

In reality, our survey results showed that students (with the exception of two issues) were happier with their housing than we expected.

As housing advisors, the staff in my office dealt with rogue landlords day after day. It wasn’t the happy students that we saw, but those with problems. However, the surveys showed us that, despite our perceptions and the dominant narrative within the wider HE sector, these problems were far from being universal. Most students found good quality housing without any problems.

This was always, with two key exceptions; affordability and the stress of actually looking for housing (especially dealing with letting agents).

Focus groups

Well designed surveys are excellent at mapping out the overall landscape of an issue. However, they often don’t answer specific questions. A survey can give you the parameters to work with in, for example, choosing sites for new PBSA (Purpose Built Student Accommodation). However, that doesn’t mean that a specific site, meeting all the broader criteria, is suitable. It’s like the algorithm of a dating site. According to all the information, you should be attracted to the person but, when you meet, it’s just not there. There’s some emotional connection that’s just missing.

That’s where focus groups come into play. The theory is that you select participants from your broader survey according to demographic criteria and then delve deeper into their emotional responses to the question you want answered.

That’s the theory but it’s easier said than done. For a focus group to work you need the person or persons conducting it to be utterly dispassionate and uninvested in the results. Within our office we once tried to solve a dispute about an issue (I seem to remember it was about whether to move all our information online or maintain some printed publications). We invited in students based on the appropriate demographic criteria and then, after feeding them pizza and generally trying to make them at ease, we went through a variety of exercises to tell us how they preferred to consume information. The problem was that the two of us conducting the focus group had very different ideas about what we wanted them to tell us. At the end, we both turned to each other and at the same time said “See, I told you so”.

It wasn’t even that we were only hearing what we wanted to hear. Listening to the tapes after, it was clear that the students vacillated between the two positions depending on who was doing the questioning. They wanted to please us both and, very clearly, read what we wanted to hear.

So, don’t get your student union to do a focus group. Don’t get your staff to do a focus group. Actually, don’t get me to do a focus group (I will always have an opinion). Get someone else who will really listen and let the conversation flow.

The two issues and what we did about them

There were two main issues that our surveys outlined to us were priorities to deal with. The first and overriding one was affordability. We chose to pursue this through two means. Firstly, we lobbied for planning changes to student housing to ensure that a proportion of all new PBSA would be delivered at an affordable rent. This subject will be dealt with in a later blog.

Secondly, we decided to create a not for profit letting agency in which we guaranteed rent to landlords for individual flats and houses. We managed their properties ( a classic Head Lease scheme in other words) whilst our staff negotiated the rent to an affordable level (using the survey results as guidelines). The students had the security and reassurance of having the University as their landlord, whilst the owner of the property had the peace of mind of having the University as their tenant. The aim was to deal with both the affordability issue and the stress for students of finding accommodation (including the issue of overseas students providing rent guarantors).

This model worked well initially but eventually fell foul of the Covid 19 outbreak. Again this project will be dealt with in another blog.

Conclusions

It is true that sometimes project opportunities present themselves which require swift decion making, and that this can make it difficult to be scrupulously thorough and impartial in gathering evidence to support a business case. However, it is also true that the best chance for a project to succeed is to make sure its premise is built on solid foundations of evidence.

That means that if senior managers want to be agile enough to take quick decisions, whilst also minimising risk, then the best strategy is to gather as much evidence as possible in advance. Regular, well designed surveys are a good way to do this.

In many cases neighbouring HEIs will also be interested in the same information, so there is always the potential to create surveys in partnership. This would have numerous benefits beyond the simple sharing of resources. For example, the combined results could be used as a lobbying tool with planners, as was the case with my surveys in London.

Whatever, the information gathering strategy is, however, there is one inescapable conclusion.

That is that there has to be one.

Leave a comment